Classrooms as Dopamine Dispensers: The High Cost of Constant Engagement

How the Pursuit of Instant Gratification Is Undermining Learning

Every summer, on the first morning after school lets out, my wife, Michelle, turns to our daughters and says the same thing:

“I am not your cruise director. My job as a parent is not to plan fun for you every day.”

She says it with love, with a half-smile, and with just enough seriousness that our girls know: she’s not kidding.

It’s not a throwaway line. It’s a philosophy.

What she’s saying, in her own way, is that parents don’t exist to entertain their children. We don’t exist to engineer their joy or pre-schedule their fun. Our job as parents is not to fill their days with endless entertainment but to make sure there’s space in their days for them to discover something deeper.

Because something happens when kids get bored.

Not right away. But eventually.

They fidget. They sulk. They complain. They say there's nothing to do. And then, somewhere past the initial discomfort, something clicks. They go outside. They make up a game. They build a fort. They start sketching, singing, reading, solving, connecting, ringing the neighbor’s doorbell and asking if their kids can come out to play.

And what they’re really doing is becoming human again, not a screen-dependent version, not an adult-scripted one, but something closer to what they’re wired to be: unique, creators, explorers, initiators, problem-solvers.

That’s what my wife is naming. And I think it’s what we’ve forgotten as teachers.

We thought more excitement meant more learning, more busyness meant more growth, and the more high-octane the lesson was the more substance it had.

And I’ll be the first to admit: I’ve done the same thing in my classroom. I still do…but I’m learning a better way.

When School Becomes the Cruise Ship

So here’s my teacher confession I’ve been sitting with for a while:

I think we might be traveling down the wrong path.

And if we are, I’ve definitely helped pave it in the schools I’ve taught at.

Schools are supposed to train students' minds to think, to reason, to question, to hold a thought, to wrestle with discomfort, and to persist. But I wonder if we’re bending the entire institution around our students’ lowest level of attention and calling it “engagement.”

If so, I’ve played right along.

I’ve designed lessons around short attention spans.

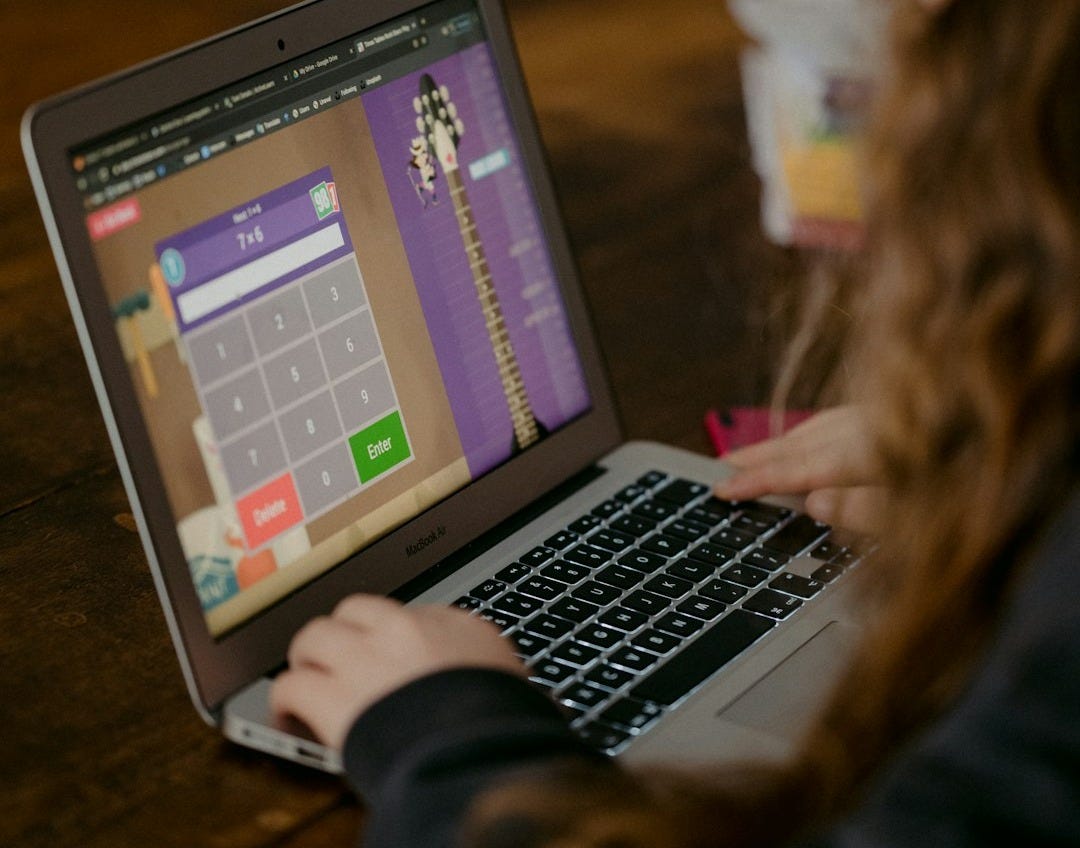

I’ve replaced boring paper with flashy screens, structure with slide decks, stamina with speed. I’ve added songs and games, flash and flair, dopamine hits and digital trivia - all with the goal of keeping kids from ever getting bored and checking out.

Because somewhere along the line, we started treating boredom like failure. And so we built a system to avoid it at all costs.

But here’s what I keep asking:

If we’re always afraid our students will disengage, are we actually preparing them for life?

The real world doesn’t award you glowing digital tokens for doing your job well. There are no brightly-colored review games to teach you all your workplace skills. No choreographed pop songs to help you prep for college exams. Your boss won’t throw digital confetti when you meet a deadline. Marriage doesn’t award “power-ups” for listening during hard conversations. Being a good parent isn’t unlocked with a cheat code. And grief isn’t gamified. It isn’t flashy. It isn’t fun. In fact most of life isn’t fun.

And here’s the thing: our students will grow up. The question is: what are we preparing them to meet?

Because if we only ever teach them to expect engagement and entertainment, we’ve failed to teach them how to push through boredom and frustration. We’ve failed to teach them the beauty of sustained thought, the dignity of delayed gratification, and the reward of hard work that doesn’t come with a prize, a badge, or an award.

And this isn’t just a classroom issue anymore. It’s a cultural one.

Haidt Was Right

In The Anxious Generation, Jonathan Haidt lays out what many of us have felt for years: kids aren’t okay. Around 2012, childhood started to shift. Rates of anxiety, depression, self-harm, and suicide began to rise, especially among girls.

The change wasn’t subtle. It was sharp, global, and deeply tied to one thing: a phone-based childhood.

That’s the term Haidt uses to describe the moment kids stopped playing outside and started scrolling inside. The moment when face-to-face interaction gave way to curated avatars and comment sections. When unstructured free play was traded for algorithmic loops of dopamine hits. When attention became fragmented and fragile. When boredom disappeared, not because life got better, but because screens got harder to put down.

And here’s the part that should wake us up:

Instead of schools pushing back on this new reality, many of us leaned in, afraid if we didn’t “keep up with the times” we wouldn’t serve our students well in the modern tech era.

We digitized everything. We added online platforms, shiny apps, and fun review games like Kahoot, Gimkit, Blooket, and more - each one promising to keep students hooked. And we believed that if they were more hooked, they’d be more engaged. But we never stopped to ask: engaged in what, exactly?

And the more we did it, the more we created a model of school that looks and feels like social media - short bursts, fast-paced, flashy wins, and surface-level thinking.

And then we wonder why kids can’t stay with a singular thought.

Why they say they’re bored five seconds into silence.

Why they reach for a device the second there’s nothing to do.

We’ve trained them to expect constant stimulation, and then we blame them for not having stamina.

Lenore Skenazy and the Radical Power of Doing Less

And this is where Lenore Skenazy’s work matters more than ever.

She’s spent years not just diagnosing the problem, but building real-world solutions that help parents and schools give kids their lives back. Her organization, Let Grow, is built on a single, countercultural idea:

“When adults step back, kids step up.”

It’s simple. But it’s revolutionary.

We don’t need another program. We don’t need more tech. We don’t need to invent another system of rewards. We need to trust kids enough to let go and let them be kids.

Let Grow Play Clubs, like the one we started at my school offer that freedom in its purest form: no screens, no structured activities, no adult direction. Just open space, unhurried time, and the kind of freedom that’s become rare - a break from constant stimulation, noise, and the pull of addictive screens.

And the results?

Kids who used to explode in frustration now mediate their own conflicts.

Quiet students find their voice.

Behavior referrals drop.

Math and reading scores go up, not because we’re drilling more, but because kids are calmer, more confident, and more connected.

They’re not waiting to be entertained anymore. They’re showing up as people.

Not because we added anything.

Because we backed off.

Because we decided that before and after school at least, we are not their cruise directors.

Because we believed that what they needed wasn’t more from us, it was more room to become themselves.

So What Do We Do Now?

If you’ve made it this far, maybe you feel what I’ve been feeling too.

The subtle ache that we’ve gotten off course.

The sense that something essential is slipping through our fingers.

The fear that we’ve traded away too much in the name of “progress.”

And the quiet conviction that maybe there’s still time to get it back.

So what now?

We don’t need to throw out every tool. We don’t need to pretend screens don’t exist or ban every dopamine-triggering moment from the classroom. That’s not the way forward. But we do need to recalibrate.

We need to remember that we’re helping tiny humans grow into healthy independent adults - not constructing robots who will need constant input, programming, and direction.

If you’re a teacher:

Give students problems worth sitting with. Fight the urge to entertain. Don’t be afraid to make them work for it. Trust that their minds are stronger than we’ve led them to believe. Sneak in a few extra minutes of recess.

If you’re a parent:

Stop curating every moment. Let them be bored. Let them wander a bit. Let them discover what they like. When they come to you with “I’m bored,” don’t rush to fix it. Just smile and say, like Michelle does, “I’m not your cruise director.”

That’s not neglect. That’s preparation.

If you’re a school leader or policymaker:

Reclaim recess. Start a Play Club. Stop cutting the things that make school human in the name of raising scores.

Because the data is already clear:

When kids have space to play, everything else gets better.

And when we protect boredom, real boredom, the kind that comes before wonder, something deeper begins to grow.

Let Them Be Bored

This isn’t a call to lower expectations. It’s a call to raise them in the right direction.

We don’t need more engagement hacks. We don’t need brighter games or shorter lessons or better digital platforms. We need to build what actually lasts:

Focus that outlives the feedback loop.

Creativity that starts from stillness.

Resilience that doesn’t need to be rewarded.

Minds that can sit with something hard and stay.

That doesn’t come from being constantly entertained.

It comes from being formed - slowly, quietly, over time.

And the first step?

Might just be letting them sit in the silence.

Letting them feel the stretch.

Letting them say, “I’m bored” and not fixing it.

Because boredom is not a failure.

It’s the birthplace of something better.

Let them be bored.

It might be the most engaging thing we’ve done in years.

One of the best things I did in my classroom this year was incorporate Figure It Out Friday. It is some type of extended word problem, logic puzzle, or real life math scenario that requires my students to combine skills they’ve learned this year. And I’ve told them, “If you solve it in two minutes, your answer is likely incorrect because these problems require thinking.” And then I sit back. And it has been so fun to watch them grown in their ability to do this over the last nine months.

I’m a principal at a small K-12 private school and currently really wrestling with these ideas. After reading The Anxious Generation, we implemented a phone-free policy and started Let Grow Play Clubs, and it’s been amazing. But it feels like the next natural questions have to do with the implications of the 1:1 school (which we currently are) and just how much our classrooms are still feeding into the problem we’re trying to address by going phone-free and starting play clubs.

It’s been interesting taking small steps away from this gamified model and seeing the kinds of tensions and pushbacks that arise. Looking forward to more work like yours - and Skenazy’s and Haidt’s - to help think through some best ways forward.